Modern astrology, in its usual presentation within magazine horoscope columns, places a lot of emphasis on the significance of signs of the zodiac. Most people know their “zodiac sign” and a few choice keywords associated with that sign – Virgos are analytical, Capricorns work too hard and so on. In fact, when somebody claims “I’m a Taurus”, what they actually mean is that the Sun was in the sign of Taurus on the day they were born. On that same day, all the other planets would also have been in various signs, but the Sun sign has the unique advantage that it is not necessary to know the year of birth to calculate it – if you were born on 15 May, regardless of the year, the Sun was in Taurus on that date, which makes it very easy to memorise your Sun sign, or simply look it up in a short column in a magazine.

Medieval astrology, however, did not place nearly so much emphasis on signs. Planets were seen as the active agents in a chart, and they were stronger in some places in the chart than others, and each planet had its own personality traits – Saturn was sombre and Jupiter generous. Saturn and Mars were considered malefic planets with a negative influence, while Jupiter and Venus were benefic positive planets. Many of these characteristics have made their way directly into the English language – martial arts and martial law derive from Mars’ warlike demeanour, jovial from Jupiter’s (or Jove’s) generosity and general beneficence, and venereal disease from Venus’ lustful traits. Methods were used to identify the strongest planet or planets in a chart, and the characteristics of that planet were used to describe the person or event that the chart represented. Hence in medieval astrology, rather than a person being described by their Sun sign, they might be described as Saturnian, relating to the strongest planet in their chart.

There were five techniques for determining planetary strength, called dignity, used by medieval astrologers, although their provenance is earlier and are described by Ptolemy: sign rulership, exaltation, triplicity rulership, terms (also called bounds), and faces.

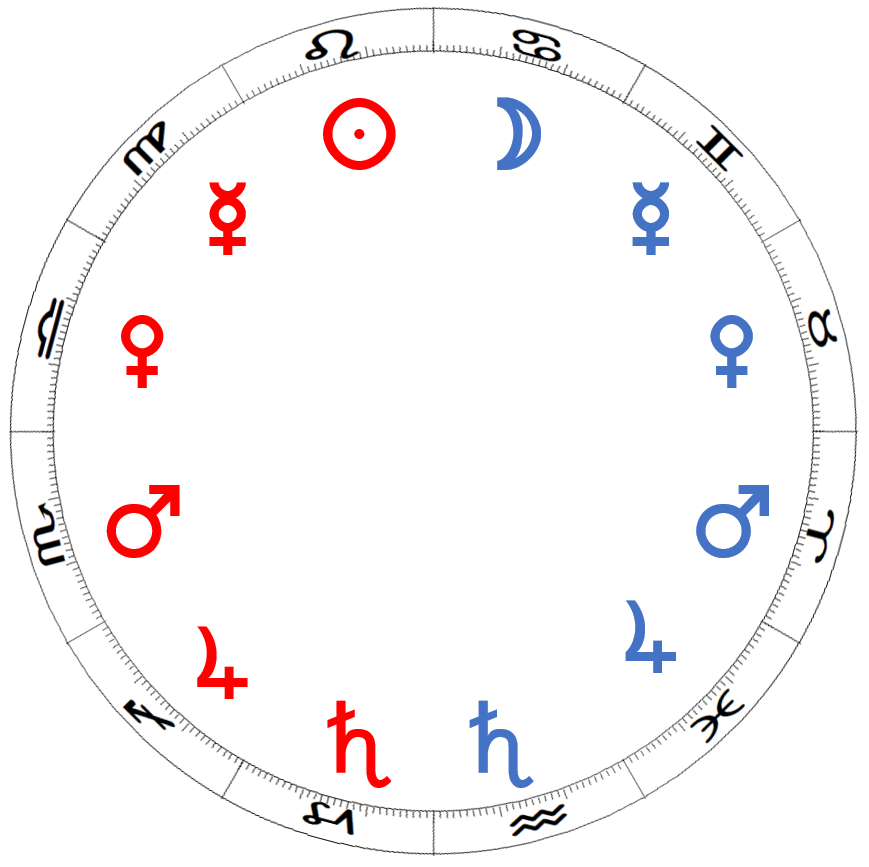

Sign rulership is the strongest of these. There are seven planets and twelve signs (planets beyond Saturn weren’t known to medieval astrologers), but two of these planets have special significance as the lights – the Sun and the Moon. The Sun is given rulership of the sign Leo, and the Moon rules the adjacent sign Cancer. This leaves five remaining planets and ten signs, and so each planet is given two signs to rule: Mercury, the fastest moving, is given rulership of Gemini and Virgo, the two signs closest to Leo and Cancer; Venus, the next fastest moving, is given rulership of Taurus and Libra, the next signs out and so on in a symmetric pattern.

Any planet in a chart that is in the sign that it rules is particularly strong. If a planet is in the sign opposite to the one it rules – for example, if Mars is in Taurus or Libra – the planet is said to be in detriment, and therefore weak.

The next strongest dignity is exaltation. Unlike the elegant symmetry of sign rulership, there is no obvious logic to exaltation. Saturn is exalted in Libra, Jupiter in Cancer, Mars in Capricorn, the Sun in Aries, Venus in Pisces, Mercury in Virgo (which it also rules), and the Moon in Taurus. Many texts even assign precise degrees to exaltation – the Sun is exalted in all of Aries, but particularly at 19° of Aries. If a planet is in the sign opposite to the one in which it is exalted – for example, if Mars is in Cancer – the planet is said to be in fall, and therefore weak.

By the Middle Ages, all signs were considered as being related to Aristotelian elements, as follows: Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius are fire signs, Taurus, Virgo, and Capricorn are earth signs, Gemini, Libra, and Aquarius are air signs, and Cancer, Scorpio, and Pisces are water signs. Ptolemy did not make the link between signs and elements, although he did group them into the same four sets which he called triplicities or triangles, and so rather cumbersomely referred to the “Aries-Leo-Sagittarius triplicity” instead of the simpler “fire signs”. For this reason, the elemental rulerships are called triplicity rulerships. Each element (or triplicity) has three planets ruling it. Some schemes made use of all three planets, others were more complicated and had one of the planets as the day ruler, one as the night ruler, and one as the common ruler. For our purposes, though, we just consider the three planets ruling each element, as follows:

Fire signs: Sun, Jupiter, Saturn; Earth signs and Water signs: Moon, Venus, Mars; Air signs: Saturn, Jupiter, Mercury.

Terms or bounds are unequal segments of a sign. Each sign has five such segments, each one ruled by a particular planet excluding the Sun and the Moon, and there is no obvious logical pattern to them. The origin of these terms was apparently Egyptian, and the lack of logic appears to have frustrated Ptolemy, who developed his own system of terms to replace the illogical Egyptian ones (although as he gave very little in the way of explanation of his method, the logic of his supposedly improved system is still hard to see to a modern eye), which some medieval astrologers used in preference to the Egyptian ones.

The final sort of dignity involves faces, or decanates, which are ten-degree segments of each sign. The first decanate (that is, the first ten degrees) of Aries is in the face of Mars, the next decanate in the face of the Sun, and the final decanate degrees in the face of Venus. The first decanate of Taurus is in the face of Mercury, the middle decanate in the face of the Moon, and the final decanate in the face of Saturn. The sequence of faces for each ten-degree segment proceeds in the ever-repeating Chaldean order of planets: Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury, and the Moon, so the first decanate of Gemini is in the face of Jupiter, since the previous decanate (the final ten degrees of Taurus) was in the face of Saturn.

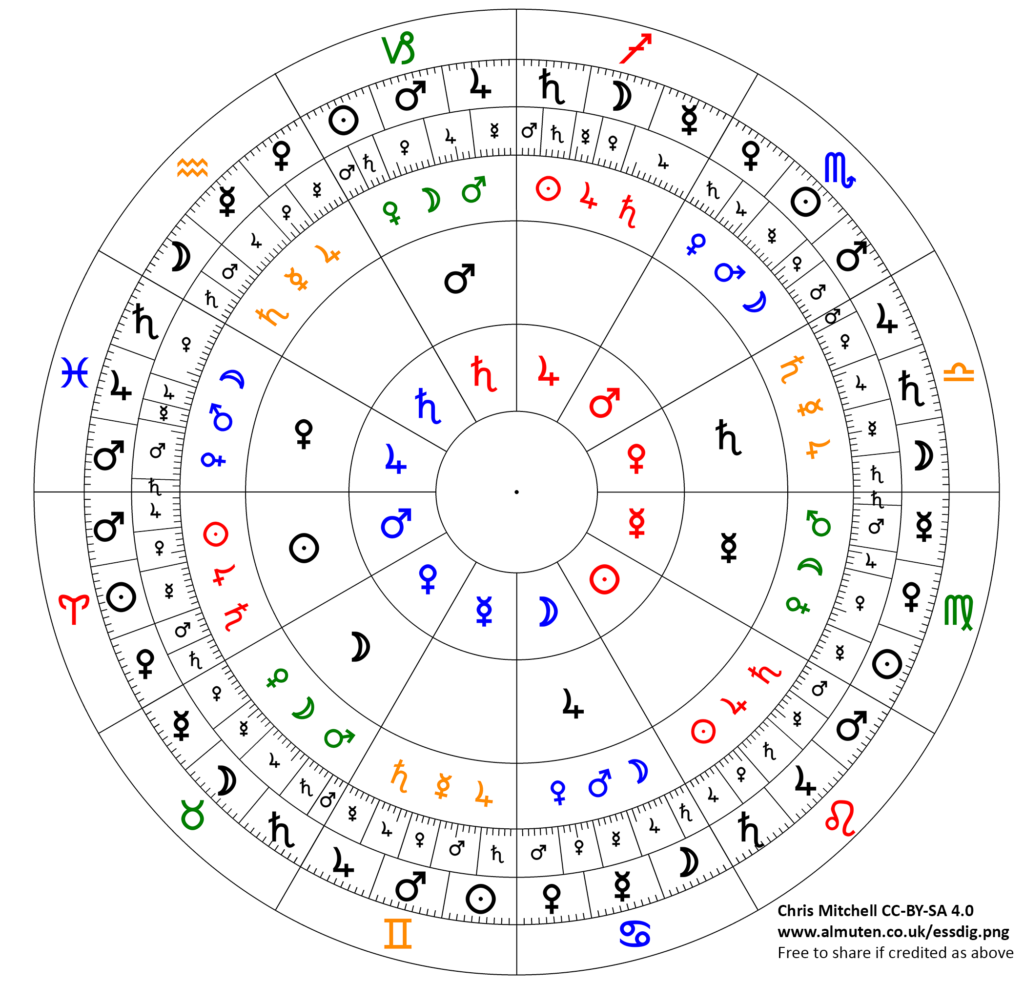

This diagram is a visual representation of all the dignities, referred to as essential dignities. The outermost ring shows the signs and each degree marked with a tick. The red and blue planets in the central ring show the signs ruled by those planets; the next ring out shows the exaltations of each sign; the third ring out shows the three triplicity rulers, colour-coded by element, the fourth ring out shows the term rulers; and the outer ring shows the face rulers of each ten-degree segment.

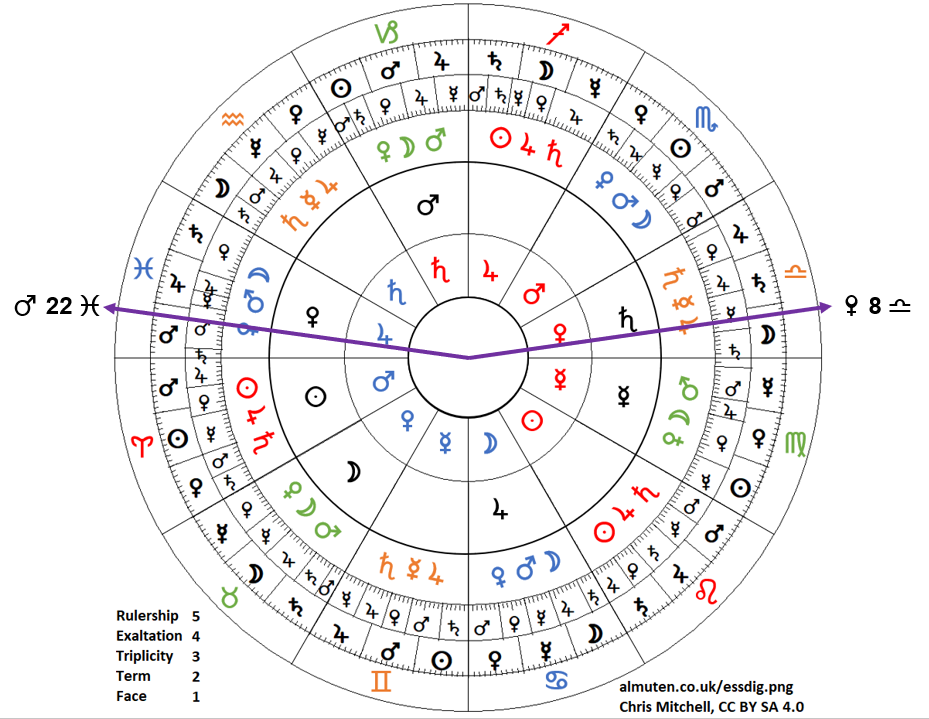

How do we use this rather complicated looking wheel? Well, consider this example: Sue has Venus at 8 Libra and Mars at 22 Pisces. Which planet is the stronger of the two? The obvious answer would be that Venus is, since she’s in rulership in Venus, whereas Mars has no clear connection to Pisces. However, let’s take a closer look.

To use the wheel shown here, draw a line from the centre point to the place on the zodiac where each planet is. In this diagram, I’ve just put in Venus and Mars for the above example.

For each planet, we see how many times it appears in the line drawn from the centre, and score accordingly. Let’s start with Venus: the purple line goes from the centre to 8 Libra. The first ring it goes through is the rulership ring: does Venus rule Libra? Yes, Venus is shown in that ring, so she scores 5 points. Next out is the exaltation ring: is she exalted in Libra? No, Saturn is, so Venus scores no extra points here. Next out are the triplicity rulers: is Venus one of the three triplicity rulers of air signs? No, they’re Saturn, Mercury, and Jupiter, so again Venus gets no extra points. Next out is the term ruler: is Venus the term ruler of 8 Libra? No, that’s Mercury, who is term ruler of the segment from 6 Libra to 14 Libra. Finally, the outer ring shows the face ruler of the 10-degree segment of 0 to 10 Libra: Moon, not Venus. So Venus has a total of 5 points, for rulership. Now we do the same with Mars. Mars gets no points for rulership or exaltation in Pisces, but he is one of the three triplicity rulers of water signs, so he scores 3 points. Moving out another ring, is he the term ruler of 22 Pisces? Yes, he is – he rules the segment from 19 Pisces to 28 Pisces, so he gets an extra 2 points. Finally, moving out one more ring, is he the face ruler of the last 10 degrees of Pisces? Yes he is, so he gets another 1 point. Altogether, then, Mars scores 6 points as opposed to Venus’ 5, so – perhaps surprisingly – is the stronger of the two planets.

This wheel makes it easy to spot dignity: if you look along the purple line for Venus, you can only see Venus appear once, in the rulership ring. If you look along the purple line for Mars, you can see Mars appear three times, for triplicity, term, and face. Try this with your own planets and see which ones are particularly strong. If a planet has no dignity at all, it is said to be peregrine and acts independently, sometimes recklessly; it’s a planet without support.

Note: you can download and print out this wheel. Feel free to share it, but please copy the credit and link.

As touched on above, the system described above isn’t the only system of dignities. This system has three triplicity rulers, all of which have dignity in their element. Another system just has two triplicity rulers – one in a night time chart, and another in a daytime chart. In addition, the terms or bounds here are called the Egyptian terms, but Ptolemy devised his own set. You can download that version of the dignity wheel if you wish, using Ptolemaic terms and two triplicity rulers; again, please copy the credit and link. The colour coding for the two triplicity rulers in this version is that the darker of the two planets is the night time ruler.