A lot of us stay awake every New Year’s Eve, waiting to usher in the New Year. Depending on where you are in the world, this happens at a different time: the first place to welcome in the New Year is the tiny Pacific island of Kiritimati, whose midnight happens at 10:00 GMT, with New Zealand following suit an hour later. The start of most years is celebrated with fireworks from New Zealand to Hawaii as midnight struck in each time zone.

New Year’s celebrations are part and parcel of our traditions here in Britain. However, new year celebrations are relatively recent in Britain; New Year’s Day didn’t become a public holiday in England and Wales until 1974 (it has a much longer history in Scotland, though, where it has been a holiday since 1871). In fact, there is nothing particularly special about 1 January to mark the new year, and not all countries do so. Iran still celebrates the Persian New Year, which starts at the spring equinox – and the equinox, or an approximation to it, was also when New Year was recognised in England right up until 1752. In medieval England, the year began on “Lady’s Day”, 25 March. This was supposedly the day that the angel Gabriel visited the Virgin Mary to tell her she was going to give birth, the fulfilment being nine months later with the birth of Jesus on 25 December, of course. At least, that’s the medieval rationale – there is of course no evidence for Jesus being born in December, and 25 December wasn’t chosen until the year 336.

In ancient Rome, the year also began in March (hence why September, October, November, and December have prefixes meaning seven, eight, nine, and ten), but the idea of the new year starting in January was already widespread; Julius Caesar reformed the chaotic Roman calendar in 45 BCE, formalising 1 January as the start of the new year. However, the date of 25 March is significant in the Roman story, since this was the date set by Julius Caesar as the spring equinox when he introduced his calendar reforms; modern software shows that date was still a couple of days out, but no one wanted to argue with Caesar!

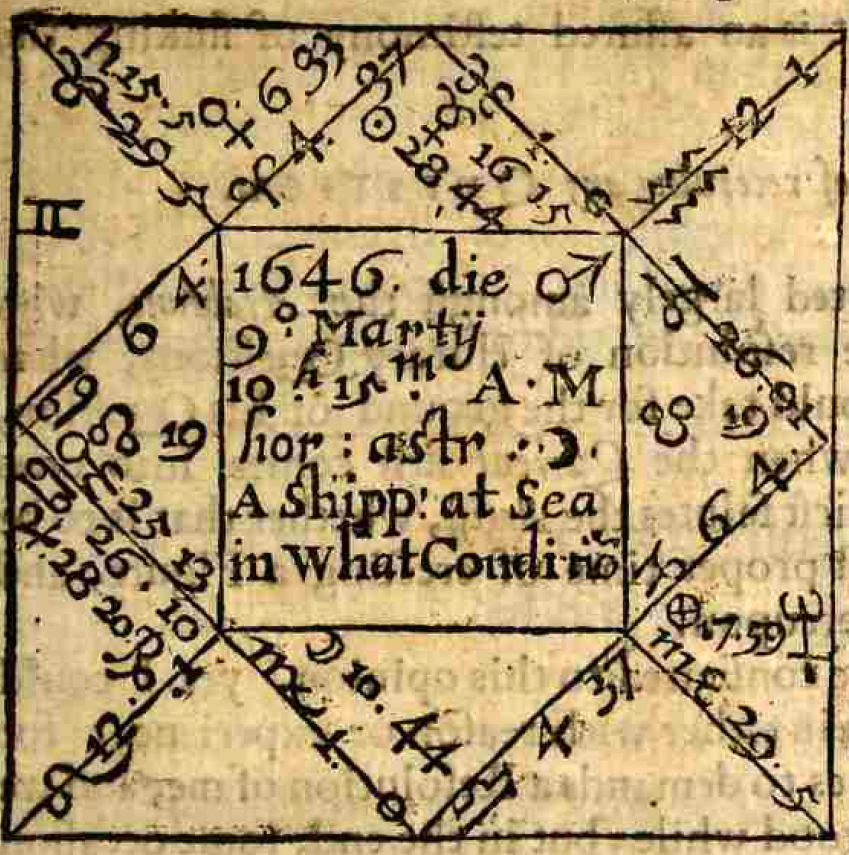

A new year starting in mid-March makes medieval dates rather confusing, of course. As an example, consider this chart from William Lilly, on page 165 of his 1647 edition of Christian Astrology.

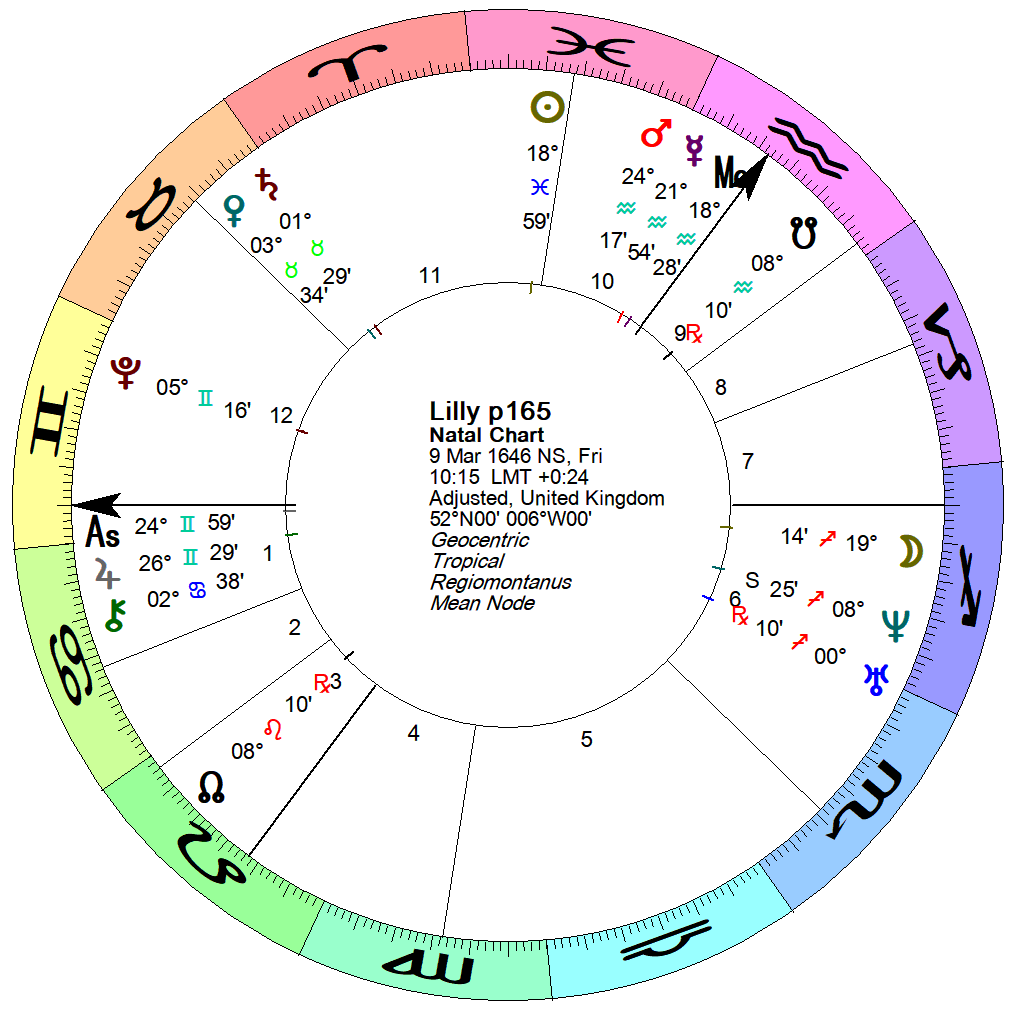

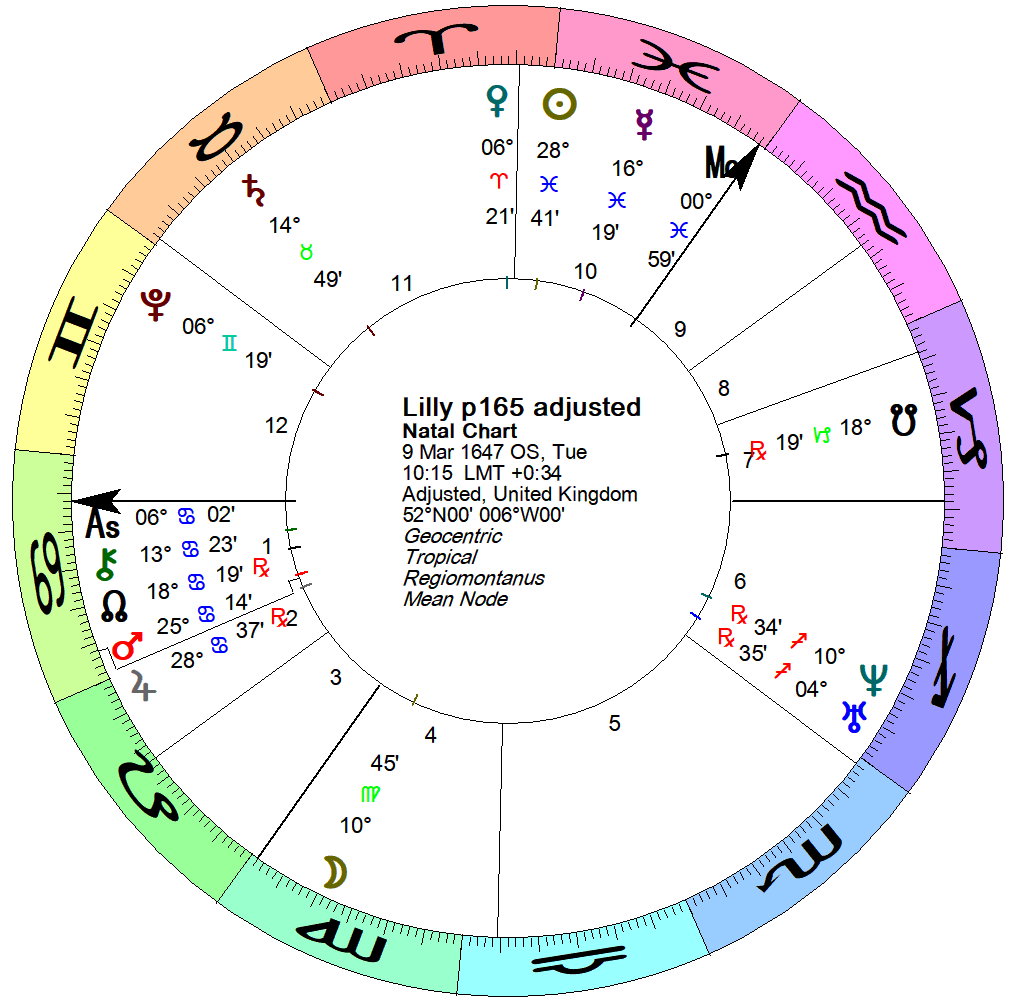

This is a horary chart to answer a question about a missing ship; the date can be seen to be 9 March 1646 at 10:15 in the morning, which he gives as the day of Mars (Tuesday). The Sun is at 28°44’ Pisces, the Moon at 10°44’ Virgo, and Saturn at about 15° Taurus. However, if we cast a chart for this date and time (I’ve set the location to 52°N, 6°W, as Lilly seems to have done this – the ship, he felt, was between Wales and Ireland, and he seems, curiously, to have used this as the location rather than the place he was when he received the question), we can see that the day is Friday, not Tuesday, the Sun is at about 19° Pisces, the Moon at 19° Sagittarius, and Saturn at 1° Taurus – nowhere near Lilly’s values. What’s going on?

The answer is that there are two things going on. Firstly, as well as setting the date of the equinox (incorrectly), Julius Caesar also implemented the “Julian calendar”, where most years have 365 days, but every four years is a leap year with 366 days. This sounds very familiar, of course, and you could be forgiven for thinking that’s the calendar we still use today. This isn’t, though, strictly true. Since there are 365.2422 days in a year, not 365.25, the Julian calendar shifts from the Sun’s actual movement very gradually. It’s not noticeable over a few centuries, but by the eighth century, the Venerable Bede noticed there was a discrepancy of about three days, and by the twelfth century it was being noticed and commented on in more detail, by none other than our old friend Roger of Hereford, in his treatise on computus in 1176. The problem with any sort of calendar reform in the twelfth century, however, is that in the absence of a printing press, trying to get churches to synchronise to a new calendar would have been all but impossible. By the sixteenth century, the drift had increased to about ten days, and a reform was finally agreed by Pope Gregory in 1582. The reform was twofold: firstly, to address the discrepancy by dropping ten days from the calendar – it was agreed that Thursday 4 October 1582 would be followed by Friday 15 October 1582. The second reform was more subtle, and designed to ensure that the calendar didn’t slip again. The rule of having a 366-day leap year every four years remained, except that every century where the year was divisible by 100, it would not be a leap year, unless the year was also divisible by 400. This means that 1600 would be a leap year as usual (it’s divisible by 400), but 1700, 1800, and 1900 would not be leap years. We today have never noticed this shift, because 2000 is divisible by 400, and so 2000 was a leap year as usual; 1900 wasn’t, but none of us can remember that, and 2100 won’t be, but most of us reading this article won’t be around then either!

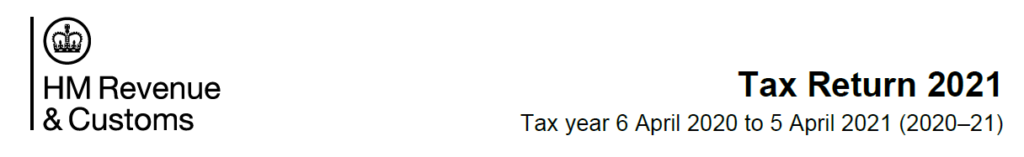

This new calendar – the “Gregorian” calendar named after Pope Gregory – is the one we use today across the world. However, not everybody adopted it at the same time. England had split away from Rome in 1534 under Henry VIII, and so was not having any truck with this “Catholic” reform, and stuck doggedly to the Julian calendar until 1752, by which time the discrepancy had increased to eleven days, and King George II finally signed a bill adopting the Gregorian calendar in 1751. This bill made three changes. First, the new year was changed from 25 March to 1 January. What does this actually mean? This is where it gets weird: in England, 31 December had always been followed by 1 January, but the year number didn’t change. Thus, to take the year of Lilly’s example chart, 31 December 1646 was not followed, as we might expect, by 1 January 1647, but by 1 January 1646. About seven weeks later, it would be 24 March 1646. The following day would be the new year, so 24 March 1646 was followed by 25 March 1647. Very strange indeed! The bill of 1751 meant that 31 December 1751 was followed by 1 January 1752 – the first time that the year number changed on 1 January. The second change was that eleven days were dropped, so that Wednesday 2 September 1752 was followed by Thursday 14 September 1752. The final change was the rule that years divisible by 100 would not be leap years unless they were also divisible by 400; this, of course, wouldn’t be noticed until 1800, which was not a leap year. The dropping of eleven days didn’t cause riots on the streets, as has sometimes been imagined, but traders refused to pay their taxes early. Taxes were due on Lady’s Day, 25 March, and dropping eleven days meant paying taxes eleven days early. The Inland Revenue gave in, and moved the tax year forwards eleven days, meaning the new tax year was to start on 6 April instead – the date that still remains today!

Some other countries took even longer to adopt the Gregorian calendar – the Russian Orthodox Church has never accepted it, which is why Christmas Day will be 7 January 2022 in Russia – a public holiday. When Russia became the USSR, it did adopt the Gregorian calendar, in 1918, and still uses it for non-religious events.

Let us now return to Lilly’s chart, and its huge discrepancies. When calculating a chart using astrology software, some years are ambiguous. Solar Fire, for instance, has a rule that if the date is after 4 October 1582 then it is a Gregorian date (or “NS” for new style), and if on or before that date, it is a Julian date (or “OS” for old style). This means that by default, Solar Fire will assume that Lilly’s date of 9 March 1646 is new style; you can change this by entering “9 March 1646 OS” as the date, telling Solar Fire that this is an old style date, since England didn’t change until over a century later. However, the chart still isn’t correct – Saturn is a good 15 degrees out – because remember that the year number didn’t change until 25 March. So when Lilly says “9 March 1646”, this is actually what we would call 1647. Solar Fire can’t cope with the year changing on 25 March, so you do need to enter “9 March 1647 OS” to get the correct chart – and that does the trick.

The moral of this story, then, is that 1 January is not a new year everywhere, and when looking at historic charts, beware of the pitfalls!

Happy new year!

Note: thank you to Mark Cullen for pointing out a confusing passage implying Julius Caesar had set the date of the equinox as the new year. In fact, Caesar specified 1 January as the new year, and this article has been updated to reflect this.